Tiny helpers—modern medicine gets a wriggle on

Expert reviewers

Essentials

- Maggots, leeches and parasitic worms can be used to treat a range of health issues.

- The success rate of using these creatures is often far greater than that achieved by more ‘modern’ medical methods.

- Overcoming the ‘yuck’ factor will open the way for these types of therapy to gain broader acceptance.

- Researchers are trying to understand and identify the different compounds these creatures secrete, enabling them to synthesise versions for future non-invasive treatment.

- Patients should never self-administer maggots, leeches or parasitic worms without medical guidance and supervision.

Maggots, leeches, parasitic worms … aside from all being a bit cringe-worthy, what else do they have in common? Well, they’re all used by medical professionals to help treat a range of illness and injury on human patients. It may sound a little gross—maggots eating your flesh, leeches sucking your blood and worms multiplying inside your intestines—but to refuse these forms of bio-surgery and biotherapy could be far worse, involving amputation, haemorrhage and death.

We like to think of hospitals as clean, sterile and hygienic. But more and more frequently you’ll be finding a range of creepy-crawlies taking up residence in your local health clinic—not as pests, but as vital parts of the medical kit.

The use of these critters is known as biotherapy—the use of living animals to aid in medical diagnosis and treatment.

Maggot therapy

If maggot therapy sounds medieval, that’s because it is. It has been around for hundreds of years as a form of cleaning wounds and helping them to heal. It was routinely performed by thousands of physicians well into the 1930s, but it fell out of favour around WWII with the introduction of antibiotics and advancements in surgical procedures. It was still occasionally used in the decades between then and now, but only if modern methods failed. It is only recently that maggots have begun to be welcomed back by some sections of the medical community.

In fact one of the greatest challenges of maggot debridement GLOSSARY debridementthe medical removal of dead, damaged, or infected tissue to improve the healing potential of the remaining healthy tissue. therapy (MDT) is changing the perceptions of doctors—many still find it ‘yucky’, if not outright repulsive and primitive. However, once they have used it once, they are often quickly converted and happy to perform the procedure again.

MDT—also known as larval therapy—is the therapeutic use of maggots (live blow fly larvae) to treat soft tissue and other skin wounds. It is generally undertaken in a controlled environment by licenced medical practitioners. The procedure involves the application of ‘medical grade maggots’ (that is, specially bred, germ-free larvae) of specific fly species to the wound site.

These maggots are interesting in that they won’t dissolve or feed on healthy tissue—they’re only interested in eating dead flesh. In this way, doctors don’t have to worry about them damaging healthy tissue or moving to other parts of the body. The maggots remain on the wound for 2-3 days, confined by specialised dressings to keep them from moving away from the wound or beginning their transformation into flies.

Studies into the use of medical-grade maggots on wounds have identified three key benefits:

- They debride (clean) the wound by dissolving dead and infected tissue with their proteolytic, digestive enzymes

- They disinfect the wound and kill bacteria by secreting antimicrobial molecules, by ingesting and killing microbes within their gut, and by dissolving biofilm

- They stimulate the growth of healthy tissue.

Additional benefits include the low cost of treatment (particularly in comparison to surgery), a high safety record, effectiveness, and, in the case of chronic ulcers, a marked reduction in odour from the wound.

Since the 1980s, MDT has proven, through numerous studies, to be ‘a simple, efficient, non-invasive and cost-effective means to debride chronic wounds…’ Many medical staff have been surprised at the efficiency of these small creatures and the success they have had in cleaning wounds.

Although many of the medical staff were sceptical and had preconceived ideas regarding MDT, they were surprised at the results this seemingly archaic therapy could achieve within just a few days.Geary et al., Maggots Down Under (2009)

MDT can be used for the treatment of a range of necrotic GLOSSARY necroticDead. For example, necrotic tissue is dead tissue skin and soft-tissue wounds, including chronic pressure ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers, venous stasis ulcers GLOSSARY venous stasis ulcerswounds that are thought to occur due to improper functioning of venous valves, usually of the legs (hence leg ulcers). and non-healing traumatic or post-surgical wounds. Matching the right wound type to this therapy can achieve a remarkable result in a short period of time for the patient.

Despite the reservations of some patients, MDT is not generally painful. Maggots don’t have teeth, and therefore they cannot ‘bite’. Instead, they have modified mandibles called ‘mouth hooks’. Their bodies are also covered in small rows of hooks which assist them to move around. The mouth hooks and body ‘armour’ assist in breaking up the dead tissue and biofilm, helping to clean the wound and permitting further penetration of the proteolytic enzymes GLOSSARY proteolytic enzymesa group of enzymes that break the long chainlike molecules of proteins into shorter fragments (peptides) and eventually into their components, amino acids as the maggot moves past.

Around 5-8 larvae are applied per square centimetre of wound surface area. The maggots are generally very small when they’re first applied to the wound, and many patients can't even feel them. Some patients who have exposed nerves in the wound or are particularly sensitive may feel some discomfort and pain as the larvae grow and become large enough to be felt moving throughout the wound site, but this can be alleviated with pain medication.

Within 2-3 days the maggots have reached maturity and ceased feeding. This means they have also finished secreting their tissue-dissolving enzymes and are keen to leave the wound site. This is useful for doctors as the majority of maggots literally fall away from the wound when they remove the dressing. Those that do remain can be flushed out with saline or removed with tweezers. For those final larvae who may be hiding in a crevice or fold, a moistened gauze over the wound will bring them out of the wound within 24 hours.

Once the maggots have been removed from the wound, they need to be disposed of like other forms of contaminated waste. Although they are germ-free when they enter the wound, they become contaminated during their stay in the body, and must be destroyed. Quarantine issues are another reason they must be destroyed—authorities do not want, for example, a New South Wales strain of Lucilia sericata being released into other regions of Australia. And besides, who really wants more flies at their family BBQ?

MDT is currently used in more than 25 countries, with approximately 50,000 treatments applied per year. Humans are not the only recipients—veterinarians also use MDT on animals.

In 2004 the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved certain types of medical maggots for use in the US. In Australia, the treatment was first used in the late 1990s. Since 2004 it has been used consistently in major hospitals, medical centres, nursing homes, home care and vet clinics around the country, though is still not a routine treatment. Some doctors and nurses, initially hesitant to use MDT, have been swayed in their objections due to the positive results and outcomes for patients.

But before you happily let a fly land on your newly cut finger, consider this. Not all flies are created equal. The type of maggot and the conditions in which they infiltrate the wound are important factors in determining whether the resulting infestation is mutually beneficial to both host and parasite. Naturally occurring myiasis (when maggots infest humans or other living animals) can be either beneficial or harmful depending on the conditions, so best see a properly trained doctor for your treatments rather than doing it yourself!

Leech therapy

Leech therapy—known as hirudotherapy—is also coming back into use amongst the medical community. Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising—leeches have been used since ancient times to treat a range of medical conditions ranging from headaches to haemorrhoids. The Egyptians were using leech therapy 3500 years ago as an important part of their healing toolkit. It was a popular treatment again in the Middle Ages and had another resurgence in the 1800s.

As with maggots, the use of leeches declined with the invention of modern pharmacology, in particular anti-coagulant GLOSSARY anti-coagulanthaving the effect of retarding or inhibiting the coagulation of the blood drugs. However, researchers are once again returning to these unique creatures. The reason? The specialised cocktail of active substances produced by leech saliva remains in many cases more effective that any synthetic substitute.

Leeches remove blood (phlebotomise) from their host, and in the process release pain-reducing and blood thinning substances in their saliva.

Leech saliva contains hirudin, a small protein that is a powerful anti-coagulant. It is one of the substances that stops your blood clotting and allows the leech to continue drinking an uninterrupted flow. The benefits of leech therapy are often not so much from the blood the leech removes while feeding, but from the biologically active substances that are injected into the host during feeding, and the continued bleeding that occurs after the leech has been removed. This is due to the remains of the hirudin in your system. Along with hirudin, leech saliva also contains 14 other active ingredients that exert anaesthetic, anti- inflammatory, vasodilating GLOSSARY vasodilatingthe dilatation of blood vessels, which decreases blood pressure and antibiotic effects, which have a therapeutic benefit to the host.

In the 1980s leeches were increasingly used by plastic surgeons who applied them to relieve venous congestion GLOSSARY venous congestionWhen arterial inflow is greater than venous outflow. When venous outflow is obstructed by clotting or disruption of veins, venous pressure increases. . When a severed finger is reattached for example, it is often possible to reconnect the larger blood vessels, but far more difficult to do the thinner vessels. This can result in swelling and pressure, which can stop fresh blood entering the reconnected area. If this persists, the reattached digit can be at risk of necrosis GLOSSARY necrosisThe death of cells or tissues from severe injury or disease, especially in a localized area of the body. (death). Leeches are used to drain the affected area and reduce the pressure.

Today, leeches are used to treat a variety of other medical conditions. These include, but are not limited to:

- abscess

- skin grafts

- haematoma (bruising)

- venous disease

- arthritis of joints

- tinnitus

- cauliflower ear

- peripheral circulation disorders

- osteoarthritis.

Leeches used in medicine are known as Hirudo medicinalis, and are a type of segmented worm. At each end of their body they have a ‘sucker’. The sucker at their rear assists them to hold their body in position, move on dry land and to attach to their host. The front suction cup contains the mouth with three muscular sets of sharp jaws, located at the 12 o’clock, 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions. They use these jaws to make a small incision in your skin and cut the underlying capillary bed. This causes your blood to pool. The leech uses the outer rim of its front sucker to create a strong seal around the wound so that it can easily suck the blood into its gut. The resulting bite mark is usually small, not particularly deep, and distinctively Y-shaped.

Leech therapy—whether it is appropriate, how long it takes and how effective it is—varies from patient to patient. People with haemophilia, those who already take blood-thinning medication, who are anaemic, pregnant, or have allergies to foreign proteins, are some of the patients who are not suitable for this type of treatment.

A treatment session can last between 20 minutes and two hours, and ends when the leech detaches itself from the host. The wound is then dressed to prevent infection, though this dressing needs to be changed regularly as bleeding will continue for several hours due to the hirudin protein, as well as the other chemicals in the saliva that prolong bleeding.

Side effects can include discomfort during the treatment, itchiness and inflammation around the bite mark and prolonged bleeding. Infection as a result of the leech bite can also occur (though this is less common), and should be treated with antibiotics.

But don’t head down to your back pond looking for leeches just yet. As with the maggots, it’s not recommended to try this type of treatment without proper medical supervision. If removed incorrectly leeches can regurgitate the contents of their stomach back into the wound, potentially causing a serious infection. You also need the right kind of leeches, trained professionals who know where to apply them, and how many to apply.

Intestinal worms

While intestinal worms are often the unwanted souvenir of many a wayward traveller, for patients suffering from inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease, multiple sclerosis, asthma, coeliac disease, ulcerative colitis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), these little wrigglers may provide some much-needed relief.

Helminthic therapy involves deliberately infecting a patient with parasitic worms from the helminth family, such as hook worms, threadworms and whipworms. The worms live within their host, from whom they derive their nutrients and energy.

But how could having a parasitic worm inside your gut possibly help? The answer may lie in the way that certain parasites—particularly helminths—have evolved. In our highly sanitised society it’s easy to forget that these little wrigglers have co-existed with humans for millions of years, and have played an important part in our body’s ecosystem over this time.

To successfully survive in the human gut, helminths needed to develop sophisticated strategies—that is, methods of ‘convincing’ the immune system to let them stay rather than attacking them. Over time, a mutually beneficial deal was worked out. Essentially, the worms secrete proteins that modify and regulate their host’s immune responses. This stops the immune system from expelling them (good for the worms), with the added benefit of lessening the body’s autoimmune response to antigens GLOSSARY antigensToxins or other foreign substances which induce an immune response in the body, especially the production of antibodies. , which in turn reduces inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract (good for the host).

Mutualistic helminths help regulate immune function, stimulating our body to build regulatory networks of immune cells that decrease general inflammation without hurting our immune system’s ability to respond to danger. In addition, these helminths produce their own array of anti-inflammatory molecules and give our immune systems much needed exercise, all of which decreases inflammation.William Parker, Associate Professor of Surgery at Duke University

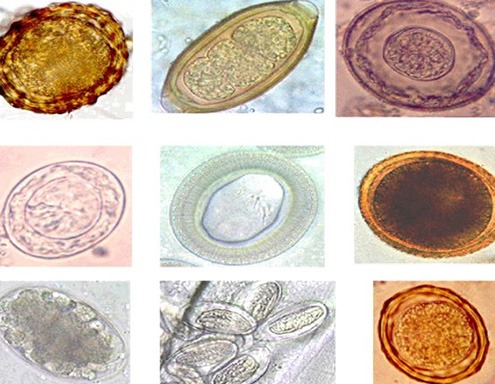

Various helminths are being investigated as potential treatment options.

| Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|

| Trichuris suis ova (TSO) | Pig whipworm eggs |

| Necator americanus | Hookworms |

| Trichuris trichiura ova | Human whipworm eggs |

| Hymenolepis diminuta | Rate tapeworm |

| Ascaris lumbricoides | Human giant roundworm |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | Human roundworm |

| Enterobius vermicularis | Threadworm |

| Hymenolepis nana | Dwarf tapeworm |

Testing is ongoing, with more research being needed to ascertain the legitimacy of this kind of therapy. Early clinical trials have shown that mice and other rodents colonised with helminths do show some protection from disease such as multiple sclerosis, asthma and IBD.

But many doctors and researchers remain unconvinced. Some studies are showing interesting, and at times, encouraging results, while others have been discontinued due to disappointing outcomes and objectives not being met. Let’s take a look at some of them.

Coeliac disease

In 2014, researchers at James Cook University made public the positive results they had achieved using helminthic therapy to treat patients suffering from coeliac disease, an immune disease caused by the ingestion of gluten. It triggers an inappropriate immune reaction causing inflammation and damage to the small bowel.

The trial involved 12 participants and took place over a one-year period. Each participant was deliberately infected with 20 Necator americanus (hookworm) larvae, and then gradually given increasing doses of gluten. Within the 12 month period, those in the study went from being able to eat just one tenth of a gram of gluten a day to a final dose of three grams daily (equivalent to a medium sized bowl of spaghetti). Most importantly, the ingestion of all this gluten had no ill effects.

So how did the hookworms reduce the inflammatory response? Immunologist Dr. Paul Giacomin noted ‘In gut biopsies collected before, during and at the end of the trial, we identified specific cells of the immune system, known as T cells, that we suspected were targeted by hookworm proteins. We found that over the duration of the trial the T cells within the intestine changed from being pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory’.

The researchers then hypothesised that this response was due to proteins the worm secretes while inside the intestine. Since the trial, they have sifted through the various proteins involved, synthesised the most abundant ones and identified the most promising candidate. The next step is to identify these molecules for further testing, with the goal of creating a new anti-inflammatory drug.

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

Crohn’s disease is a chronic, inflammatory disease of the intestine. It most commonly affects the large intestine (colon) and the small intestine (ileum), though it can involve any part of the digestive tract, from mouth to anus. Ulcerative colitis is confined to colon and only affects the top layers in an even distribution.

Some of the earliest helminth therapy trials (c.2000) were based around Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Using pig whipworm (Trichuris suis) as the chosen helminth, the treatment was well tolerated and test subjects displayed significant disease remission. In 2004, another study was undertaken involving 29 Crohn’s patients who drank live eggs over a six month period. At the end of the trial, nearly 80 per cent reported a decrease in symptoms and 72 percent fell in to remission. These promising results paved the way for larger trials, which were conducted with the support of a large pharmaceutical company.

Despite the apparent success of earlier trials, the results from the first large clinical trial (which involved using TSO in 250 US patients suffering from moderate to severe Crohn’s disease) were disappointing. The study was discontinued after independent monitors concluded that the therapy wasn’t helping patients—either in terms of improving disease activity index or remission rates. Shortly afterwards, a second study (which involved 240 European Crohn’s patients) was also discontinued due to ‘lack of efficacy.’

Although these results are disappointing, the results from clinical trials involving patients taking Trichura suis ova (TSO) to treat ulcerative colitis are still to be released.

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis—a debilitating disease of the central nervous system that can affect the brain, spinal cord and optic nerves—has also been targeted by researchers as a potential candidate for helminth therapy. As with the studies of Crohn’s disease, results have alternated between studies.

Clinical trials using TSO or Necator americanus larvae to treat MS have so far been small and of short duration. The first clinical trial using TSO in the US was undertaken by the University of Wisconsin. Five recently diagnosed MS patients drank TSO every two weeks for a period of three months. As the study progressed, researchers monitored new and old lesions and spots of nerve damage, via MRI scans. The results were encouraging—lesions fell more than three-fold by the conclusion of the study. When patients ceased taking the TSO their lesions returned to their original levels. However, a second, longer trial involving 15 patients taking TSO recorded only a modest decrease in lesions.

So while preliminary magnetic resonance imaging and immunological outcomes of the therapy have been encouraging, the results must be interpreted with caution. The reasons for the caution is that trials were very small and follow up with patients after the trials ceased was limited. The long-term safety of this type of therapy also still requires attention.

Like the researchers at James Cook University, scientists are now looking at alternative approaches to live helminth therapy and exploring the identification of helminth-derived immunomodulatory molecules that mimic the protective effects of parasite infection (i.e. capable of altering immune responses).

As with other forms of biotherapy, it is important to speak to a trained doctor when considering this type of potential treatment. Patients should never self-diagnose or try and treat themselves with worms in an uncontrolled environment, as this could lead to serious health consequences.

Conclusion

Most of us are keen to swat, spray, slap or fumigate at the first sight of any perceived ‘creepy crawly’. But despite all the advances of modern medicine, we may yet discover that the solutions to many of our physical ills were always nearby. If we’re able to look past the ‘yuck’ factor, we will find that far from being banished, maggots, leeches and yes, possibly even parasitic helminths can be useful and beneficial in medical treatments.